20-1-2020

Written originally in Arabic by Maie Panaga and Sally Alhaq, translated by Nermeen Hegazi.

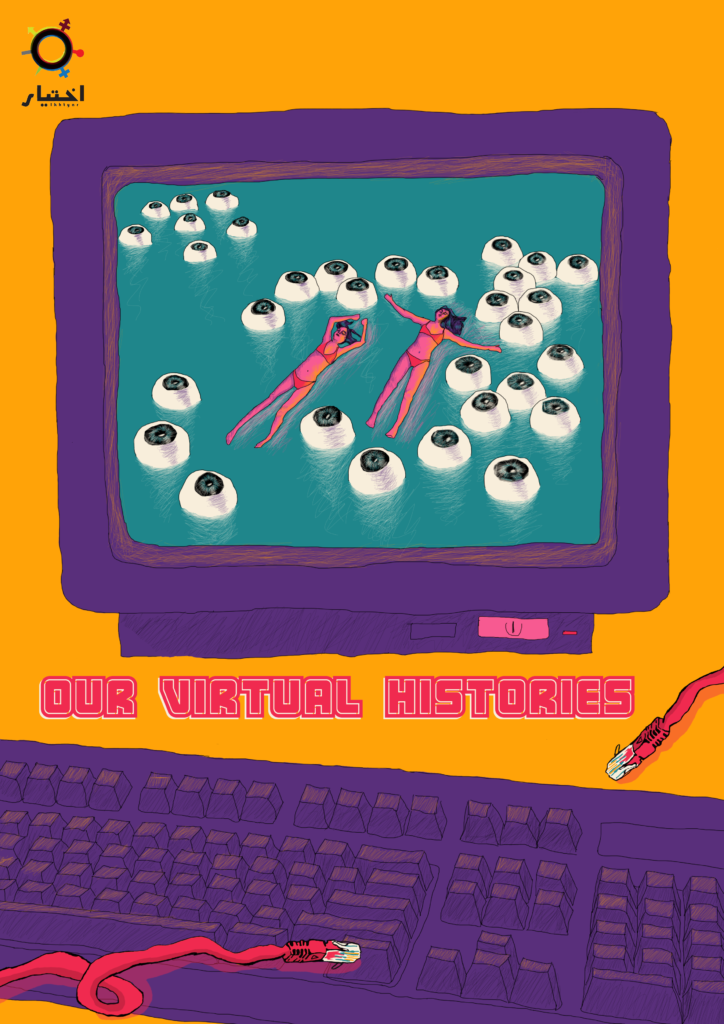

Our Virtual Histories (PDF)

Please note, writers’ voices are color-coded.

We connect to the internet in order to connect with something outside of ourselves: maybe the world, other people, a group of strangers. Maybe we do so to become part of a political movement, or to become part of those evil groups that lure innocent people into becoming commodities on the “deep web.” This is the beauty of the internet; it is broad, endless, fascinating, and dangerous. It’s a sea full of treasure — brilliant colors, danger, and many mysteries and opportunities.

The following personal reflections document the journey of two women on the internet. Through them we explore how we express (or don’t express) ourselves during various stages of our lives and during different political eras, how we search for the meaning of life, and how political awareness is shaped online. We go back to how we educated ourselves during the revolution and before it, beginning with the birth of blogs in Egypt, when our horizons began to expand to personal and political narratives, previously available only in the dark corners of the internet, followed by those with insatiable curiosity.

At Ikhtyar, we wrote a research paper that outlines the impact of digital abuse, especially cyberbullying, on feminists during the period of July 2017 to November 2018. Alongside publication of the research, we wrote this text as a way of reflecting on our personal experiences and political activity on the internet, experiences that gave us the opportunity to express ourselves outside the confines of the society in which we live and enabled us to develop an imagination that extended beyond our daily realities.

Getting to know the internet: Getting to know the self

The screen — a window on the outside world — lights up, offering an opportunity to make friends and meet strangers from all over the world.

I answered the question “ASL?” with “A teenage female from Cairo.” The screen gives me access to a world much bigger than the four walls of my bedroom and the few hours I’m allowed on the computer before it’s my brother’s turn.

The desire to express myself was changing and developed with the development of social media platforms, starting with Myspace and through to Facebook and Twitter. All these platforms asked the same question, though in different ways: “What are you thinking?” As a woman, you’re not asked this question beyond your screen. What are you thinking? What are your opinions about everything? Starting with your favorite music to changing political and social events, and even your own very personal feelings. All these have a place on the internet. There’s always someone who will listen to you, someone who will express their admiration, someone who’s been through the same experiences.

The freedom to explore my sexuality happened along with my presence on the internet. All you need is a small smartphone that’s connected to the internet and a password. And then, coming out of the closet only required a pseudonym, allowing me to explore the different geographies of pleasure the internet had to offer.

My family gave me a mobile phone to guarantee a way to communicate with me when I was outside of the house — a way to determine my route, to know where I was at all times. But the phone’s screen, small as it was, represented a window that overlooked a much bigger world, a world that existed beyond the set hours you were allowed to use the internet, beyond the snooping of parents, beyond the checking of your private search history on the family computer.

That little phone screen was the first space in which I could express myself and ask the questions I couldn’t dare ask out loud, a space that didn’t require that I check to make sure the coast was clear behind me, that there was no one peering at the screen.

We live in a social context that treats the body and the changes it goes through as top secret information. Meanwhile, our computer screens are a portal to a multitude of voices ready to answer our every question, respond to any passing thought we have. Some of these voices decry thoughts about the body as sinful; they offer ways of redemption and teach us how to fight against our bodily desires. Other voices, swathed in scientific garb, explain the female body and its desires: chemicals and hormones that develop in a natural manner. More voices interject, outlining psychological characteristics while theorizing about causes and cures. Other voices lure you down the rabbit hole: you are now Alice. All you have to do is confirm that you are of legal age — 18 or older — through a mere click of a button, for your screen to fill up with a medley of images, videos, and voices that represent everything no one else will tell you about; all the things normally kept quiet are being shouted out loud in this virtual reality.

Our presence in this virtual space, much like the real world, is divided between two spheres: the public one — through public computers in cyber cafes or the family living room, where you are introduced to the world — and a very private one, through the screen on your smartphone, which gets more and more technologically advanced year after year. Through this technology we discover ourselves, and grow and mature as a result.

An activist once joked that introverts are among the loudest people on the internet. That, in a nutshell, was my adolescence: loud online and quiet in real life. I began using the internet in my early teenage years. I’d search for information and friends. I’d ask questions I could pose to no one but Google.

I went online in the hopes of finding someone like me. I surfed the internet with no agenda in mind, with the passion and thirst of a teenager. I loved, more than anything, the online political communities that sought change, whether in Egypt or abroad. I owe them a lot when it came both to learning about myself and engaging with things outside of myself, with the entire world.

I first went onto the internet using a mouse and keyboard, which controlled the large monitor. I always wondered why the computer was so big, especially years later, when I owned my first laptop at university. The laptop was small enough to carry with me everywhere, and to hide, whether under my bed sheets at my family’s home or at useless university lectures. Nothing was quite as interesting as my little notebook computer.

What I could access on the internet differed from device to device, whether desktop, laptop or smartphone. Each one represented a different phase in my life and a different approach toward knowledge and communication. I grew along with the technological advances I witnessed.

The political side of the internet and Arabic content

My relationship with the internet as a space for discussion, expression, and education developed in parallel to the unfolding of the revolution. Social media platforms, especially Twitter and Facebook, represented an opportunity to be present in different circles discussing various issues. It was an opportunity not confined by geography, time, or the rules imposed by family, which dictated not engaging with events taking place on the ground so as not to be exposed to danger. In the virtual realm, I participated in discussions and altercations. I documented events, supported causes, and did a number of other things. This entire world was transported into my little room, situated in a home with rules that dictated where I, as a woman, should be at such a late hour.

Discussions unfolded before my eyes, imbued with things I didn’t know: words, interests, political leanings — from the far right to the far left. There existed a political and social history that wasn’t easily accessible before. I became absorbed in conversations I wasn’t able to join, and, hungry for knowledge, I followed them instead. This hunger drove me to keep up with everything being said and proposed at a rate much faster than I was capable of in ordinary life. It propelled me to make a decision about which group to join — leftists, secularists, conservatives and so on, with some women asking, quietly, where women’s issues were on the agenda.

Alongside following the discussions on Twitter, I tried to learn about this political and social history via blogs referred to repeatedly on Twitter. These blogs required a lot longer than a few hours to go through, unlike Twitter. There was more space on blogs to talk about all these different issues in colloquial Arabic, which made them accessible to people like me. People like me who hadn’t engaged before in political or social activity “on the ground,” making them realize how ignorant they were, how they lacked the time necessary to catch up on everything — whether on the ground information in the form of state violence, political analysis, setting strategies for better solutions, or imagining a future represented by the various faces and names of those who had come to be known as “political activists.” Everything that was political and collective broadened and crowded out the space that had been occupied by everything that was personal and individualistic.

As modes of access become varied and the number of social platforms increase, the internet ceases to be a mere window. It becomes a basic necessity of daily life. The world is at our fingertips and technology has come to fulfill our every need: communication, scheduling, education, menstrual cycle tracking, and time management. It can even remind you to stay properly hydrated.

Algorithms quietly prepare for you lists of your preferences, based on the search words you use and even the music you listen to. With the development of events in the public sphere, search words have developed to include feminism, the history of political and social movements, and the policies that pertain to electronic spaces and social media platforms.

I see the internet and social media platforms as a live personal archive, which documents my personal, social, and political interests, much of which have changed and matured over time, but which were, at one point, all very real to me. I remember them when I click on the back button to find an old tweet or personal post, or an old post that makes me shake my head in confusion and ask, “Who is this person?”

I am indebted to the internet and social media platforms at a political and social moment that was charged with many types of education: political, feminist, and so on. There were personal discussions between individuals of different affiliations and leanings, left-wing and right-wing, opponents and supporters. These discussions often appeared to be very intimate. They played out in a series of tweets that, at the time, didn’t exceed 140 characters. They revolved around a medley of historical and contemporary topics — a melting pot brimming with life, a circle of awareness and education. Some discussions devolved into altercations with those who posed questions or made objections. Others pointed toward a history that was older than blogs. These blogs were like a living archive, rich not only with the subjects explored in the posts, but also with the discussions that took place in the comment section, which might have seemed very personal and intimate, but on the internet, there’s always someone watching. I was part of that generation, always observing and following.

My relationship with this space changed. It transtioned from being a mere window onto the world, in which I was a consumer and explorer of this vast space, leaving easily traceable tracks behind, and became instead a space in which I formed a feminist and political awareness and had developing personal interests.

With time, and a change in the political and social landscape, discussions became more violent. You stop wanting to hold a conversation with the other side, instead you want to annihilate their virtual existence, armed with tools like “report” and “block,” which had generously become available on social platforms. Battles in the virtual realm reflect what goes on outside: a desire to empty spaces of the voice of the other, no matter who they are. The 140 characters became an invitation for combat, threats, and isolation. A weapon used by all sides, from the far right to the far left.

From 2007 to the onset of the 2011 revolution in Egypt, the only people I interacted with online were friends who, though very present in my daily life, were virtual — my “online friends.” There wasn’t anything to lose, I thought. There was enough freedom to get to know strangers with whom you had some aspects of your identity in common. Your political opinions, of course, and the books you read overlapped. I was introduced to feminism through the internet. I came across the word “queer” for the first time on one young woman’s blog. I looked it up in an English dictionary and came up with the definition “strange.” I felt strange as a person, but I didn’t understand what the word meant in the context of sexual identity. I was 18 then. I didn’t understand the theory, but it made me stop and think. I was also taking fledgling steps toward understanding Marxism, social change movements, and tracking Egypt’s political digital footprints to understand why our lives are not easy, kind of miserable, and why we aren’t supposed to live like that. This was during the Mubarak regime. After or during the revolution, things changed a bit. The activists became the lords of the internet. They were the gears that caused or magnified the spread of a beautiful kind of chaos, change, a better future, and a better, more colorful Egypt. We began to cross paths. Working in human rights became my reality. We ceased to be strangers. I began to put faces to these accounts and their stories. My face and story, too, came to be familiar to them.

The Arabic-speaking internet suffers from a lack of content related to human rights, sexuality, and gender. Perhaps, this is what we all felt was missing as our awareness was shaped by English resources, making use of the few words we knew from school, movies, and songs. Class here plays a big role in how fluent you are in a second language, especially during your adolescence. For us middle class people, we did not come to our current knowledge easily. What we are trying to do now is to create — through our collective — feminist content in Arabic, in an attempt to make the internet a more welcoming and generous space for women. That is what queer, feminist content coming out of Palestine and Lebanon did for me. It taught me the Arabic acronym for LGBTQ+. There were a lot of letters in that acronym before it evolved and became simply the “Meem” community. They made the word mithliya [homosexual] feel close to home, one that wasn’t far removed or foreign. The social media profiles of the women responsible for this content became a point of great interest for me: Does that woman really love women? Did she write that text? Is that her romantic partner? It became a quest for personal knowledge, from which we derive the power to be ourselves, and a mission to read every article, poem, research paper, or book someone recommended online. The more my goal was intimate, personal, and private, the more my quest for knowledge was exciting.

Home as an extension of the internet

The lines between the virtual world and reality, between home and digital screen, blurred. Every sentence, like, or picture became warning signs, indicating that you were straying off the path carefully laid out by family and society, straying from the image of the respectable girl with very ordinary interests and views consistent with the majority.

“Delete that picture. Your clothes are revealing.”

“Don’t share nude pictures. It’s not artsy. It’s indecent.”

“What do you mean by what you wrote today?”

Then, Twitter swooped in as the perfect solution and savior. Society’s watchful eye on Facebook could be temporarily escaped on Twitter. Twitter was full of strangers, and there was less space for explanation because fewer characters were available for self-expression. But as the events of the revolution unfolded on the ground, Twitter as a space for mindless chatter changed. It now burst with political opinions and chants. Public personalities became more well-known, more vocal and serious. When the internet was thankfully restored after a period of blackout during the revolution, the voices on Twitter returned stronger and louder than before.

Facebook became a space that brought together friends, acquaintances, and family, while Twitter had been a space for mindless chatter. Over time, Facebook expanded to become the primary platform for self-expression and a more familiar environment, and with that expansion, our skillfulness with self-censorship evolved. One’s personal thoughts and opinions now had to be scanned by family and friends. One could even be asked, outside the virtual realm: What do you mean by this or that opinion? What is the meaning of that picture? Who are these people?

This space becomes very familiar. Your opinions are shared over the phone in a conversation between Aunt X and your mother. Suddenly, you’re facing an informal investigation at home about your thoughts. You learn to play a new game, using symbolism and vague pronouns. Your different online spaces now include a “limited list” for family members, limiting their access to your profile as a way of preventing them from monitoring your activity. Until, one day, you decide that withdrawing from Facebook altogether is the optimal solution.

I don’t have a Facebook account, and I deny to my family that I have an account on Twitter. I’m now a master of symbolism, stealth, and vagueness. On other platforms I even hide behind anonymous usernames or protected accounts. I pretend not see unwelcome friend requests.

Familiar spaces in a vast geography. Surveillance, judgement, rules, and images of who we should be are normalized. Violence is familiar. It crouches in a corner, ready to pounce, to drag you back behind the lines of acceptability.

I was one of the first four girls in my family to join Facebook in 2007. One of us didn’t have to answer to anyone about anything because she was raised in America. The other two were from my mother’s side of the family and they had a chilled out father. No one in my circle at school, which was also my social circle outside of school, was on Facebook either. I created an account, curious to find a world I could interact with. Through Facebook, infinite circles of communication opened. I now also had access to other platforms, such as Goodreads, WordPress, and Diigo. Worlds opened up for me as every second I deviated, further away from everything everyone in our home believed in.

By 2012, they all knew I was on Facebook. Friend requests came from my sister and her friends, classmates, my brother-in-law, and my cousins. I responded to these requests by blocking them and adjusting the privacy settings on my accounts. I became the “ghost” that I am now. The digital trail I left behind was hard to trace; it couldn’t be followed except if I wanted it to be.

One family member, acting all macho, told me he deemed my clothing in a certain picture to be “indecent,” according to his view of what women should and shouldn’t wear. He also thought my friendly photograph with a male friend was inappropriate. Another relative was morally offended by the fact that I used the words “fuck” and “sons of bitches” in an angry post about police brutality with protesters in Egypt. The list of moral offenses goes on. I began to, unwittingly, provoke them online with things on that list, only for my offenses to follow me to a family dinner or an unwelcome phone call that messes up my entire day.

The loss of innocence: Tahfeel

“If I saw you in the street, I’d rape you,” was a response to a comment I wrote about women’s participation in demonstrations. He was not pro-regime or even against the demonstrations. He was not, according to him, against women. He just didn’t want these women’s socially unacceptable practices (such as smoking cigarettes or overnight stays at sit-ins) to tarnish the reputation of the revolution.

Another message: “I know who you are, and I will tell your family what you are.” The threat was protected by complete anonymity. It was written in response to me expressing that I’d had a good day. Apparently the shadowy account holder didn’t want to have a good day like me.

Surveillance is expanding and becoming more intense, what with new social media platform policies and restrictive state policies. But the worst kind of surveillance is community surveillance, which isolates, attacks, and threatens, under the seemingly harmless act of tahfeel. [Note: The noun tahfeel comes from the Arabic word hafla, which means “party.” Tahfeel, in essence, means to make a party out of ganging up on someone and teasing or taunting them.]

I remember that at the beginning, the reasons for bullying were clear, or perhaps, understood: it would be to do with politics, religion, and sex — or at least that’s what I thought. But in fact any opinion could turn you into a target for bullying. Maybe they disagree with your opinion or your person. Maybe it’s because they’re having a bad day and you’re the first person that popped up on their timeline. Maybe it’s because we’re women and shouldn’t have opinions that agree or disagree with anything, no matter what that thing is. Making fun or light of her opinion is the easiest option, for example by telling her to go back to the kitchen whenever she talks about anything at all. This form of bullying is used most when the topic in question is the sacred, very masculine, sport of football.

The times I can recall when I was subjected to attacks and tahfeel are not few. Before I began to think about and discuss them, I didn’t really see them as having had that much of an impact. I’d never seen myself as passive or as a victim who was forced to alter her behavior or mode of participating. But in fact, over time, a lot has changed. Now, the mere threat that something I’m going to share or say might bring me trouble or a headache forces me to wonder, even if just for a matter of seconds, whether it’s worth the consequences. If maybe instead of sharing it with the world, I should just share it, online or offline, with a smaller circle of friends.

I would also like to remind myself that I very actively contributed to the culture of tahfeel a number of times. I contributed by renarrating the contributions of others. I didn’t have to necessarily agree with their misogynistic or homophobic messages, but it was wrapped in a shiny layer of humor that often causes us to participate in a culture we’re trying to change. I did so with an ease that frightened me, and all because this culture of tahfeel was disguised as humor.

When I look back at my electronic archive during the period of 2006-2007 and compare it to the way I participate online now, I am surprised.

Anonymity no longer works for me like it did before. There was a contradiction between the desire to be seen and visible and not wanting to leave a trace or be followed. In fact, I would like to be both: visible and anonymous. I want to be compensated for all the violence that comes with the hidden parts of my identity, but at the same time I don’t want to be subjected to blackmail or objectification, which are things you can’t control when you share yourself with the world. Or at least that’s the data that’s been given to us by technology, companies, and reality thus far.

Have I been subjected to tahfeel before?

Once or twice! The first time it happened, M.P and I were tweeting on “One Day One struggle” day in colloquial Egyptian Arabic. We were talking about sexual rights, the diversity of identities, and different forms of oppression. Twitter, at the time, was wild. We were just two devout Twitter users, tweeting, laughing, loving, joking around, sharing readings, and reading the news. We weren’t “influencers.” Only those who, like us, hid from reality in the meandering alleys of Twitter, ever really noticed us.

We were angry and fueled by feminism, the violence of our reality, the ferocity of our youth. That’s when the tahfeel started. My friend received a threat of public rape from a familiar male face in the revolution. Twitter users from Egypt and the Arabic-speaking region cursed at us using the most foul language. An army of loved ones joined us, activists from here and there. We all tweeted together, hoping to drown out the attackers’ voices. Did we let them get to us? No! I was soaring, ecstatic with my words of self-expression, the danger we were facing, the support we were receiving. Maybe if we hadn’t received support from feminists we didn’t know, we would have been affected negatively.

There was beauty in the succession of tweets, advocating for freedom and rights. There was beauty in the beginning of new friendships based on the desire to change the reality of our country for women and LGBTQ+ communities. Of course, there is harm in the sense that what is being attacked is your life, and seeing a hateful tweet that will stay on the internet, bearing your name and what you are, has a cruel sort of impact. It comes from a place of hatred. But at the time, we didn’t care.

I was not affected in the beginning by the comments or attacks that came in waves. The voices of women and minorities wishing to open the debate about bodily and sexual rights, and all that, were personal at first, were quiet at first, their voices drowned in the rush of larger public and political issues. They became louder after attempts to cover up the rapes that happened at Tahrir with the flags of the revolution. The voices of sexual minorities were being raised, wondering where we were in the bigger picture. Women who talked about all that was private and intimate started raising their voices, and there were many failed attempts to make us calm down using big words and nominal representation.

S: In June 2012, women and men marching in a demonstration against the sexual harassment happening at Tahrir Square were subjected to harassment and violence. The hashtag #marchofsluts was born as a form of tahfeel against the activists and women who took part in the march and in response to the hashtags #no_to_harassment and #EndSH.

If you visit this hashtag on Twitter now, you’ll find that as we record the memory of our political movement through tags, the digital memory of the internet also records the violence and tahfeel that occurred during a political era that saw so many changes. We may forget, but the internet never does. As well as all that is beautiful, it records all that is ugly. Hashtags remind us that the internet is in fact an extension of the street, including all its violence.

#slut_march is one of the most painful moments I experienced in the history of my use of social media. Just after the first time I was mass sexually harassed, my timeline was full of that hashtag. I looked out of that window to see familiar faces, support coming from those who were like us and shared our values and enthusiasm. But we were ridiculed. What did we expect when we were demanding recognition of mass sexual assaults or an end to harassment!

The new face of the internet

From the outset, our research aimed to answer the question “Who’s today’s victim of tahfeel?” — a question you might find in a tweet or a comment on Facebook, a question asked from different accounts: a young man who is bored, an intellectual suffering from delusions of grandeur, internet users who feel like they’re better than everyone else.

We started working on our website as feminists engaged in digital rights and building the sustainability of a digital space that allows us to express ourselves, organize, and network.

We have a lot of evidence from our online experiences, and a lot of assumptions as well. We interviewed eight women of varied ages and backgrounds, interacting in different ways with a feminist discourse that discusses the reality of women’s lives and bodily and sexual rights. When we deconstructed the act of tahfeel, as usual we saw that it contains an element of privilege. One that decides who’s going to be subject to tahfeel and who won’t be. There are some internet users who engage in tahfeel indiscriminately when anyone expresses anything that disagrees with the hegemonic morals, values, and traditions of Egypt. There are class, educational, and occupational privileges combined with how important your friends and connections are that might protect you from being at the receiving end of tahfeel.

There is something sweet when movements that strive to create change cause a din online. There is comfort in tweets that flirt with you, that flow with love. Tweets that float by as a sweet, transient gesture on the world wide web. There is passion in feminist content from the Global South, as we create content that rejects, deconstructs, and resists discrimination based on gender, race, or sexual orientation. Content that seeks to hold companies and service providers to account for profiting from our data, and exposes acts of digital violence committed by other users.

I have a lot of mixed feelings about technology and the internet in general. I still love social networking sites and my changing position on it, as someone who observes the many ways younger generations make use of it, for example. I love how Twitter is often used to share personal pictures and express different ideas and leanings, despite increased societal surveillance, armed with social media policies that encourage the reporting and shutting down accounts for reasons both logical and illogical.

As we broaden our work on building feminist internet, on the responsibility service providers have toward their users, and on our collective responsibility as users and feminists, we try to imagine and implement the internet we want, with all its diversity and spaces of expression, games, validation, and communication. But we hope to do so with an awareness of the inseparable practices that women bear the brunt of. I love the internet and the learning and opportunities for growth it has provided me with, but I want more spaces where I am not afraid to express myself, where I don’t have to hesitate before pressing the post button.