Written originally in Arabic by Sara Kadry

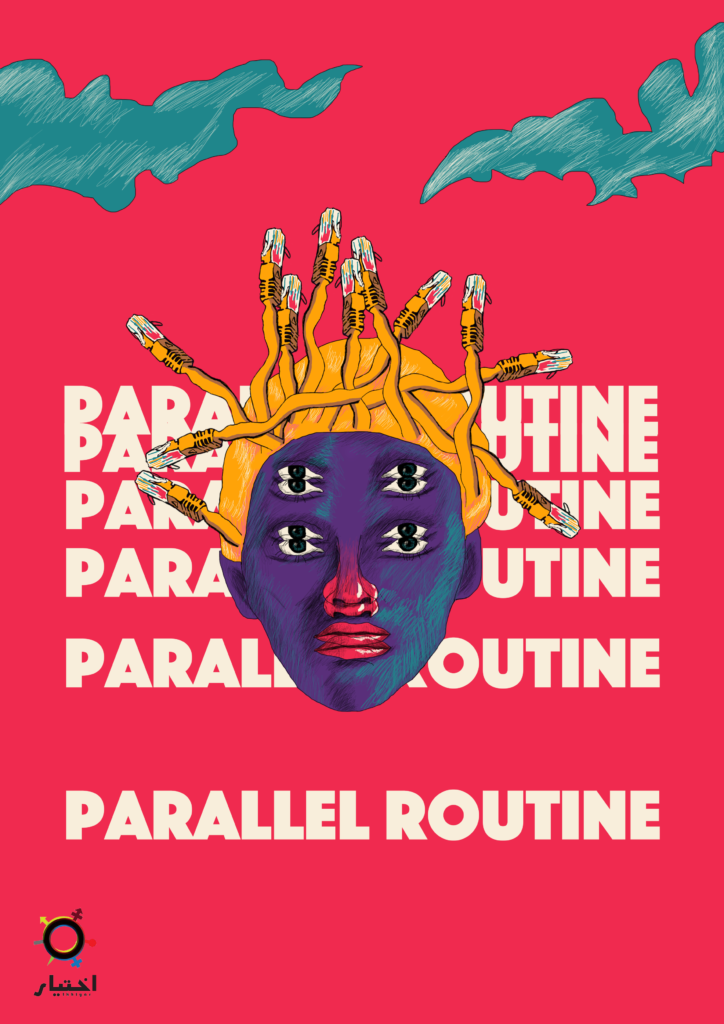

Parallel Routine (PDF)

The internet features complex, multilayered social interactions — including of gender identity, class, and sexual orientation, not to mention internet availability and access privileges. It also manifests various forms of inequality, according to linguistic and racial privileges. Digital spaces are generally affected by and reproduce all these inequalities, and this does not always take the form of outright discrimination. For example, Egyptian digital spaces are predominantly English-language which reflects and entrenches class privilege which is itself a product of a reality where educational opportunities are not equal.

Previously, believing the online to be an open space that allows users to participate and express themselves freely, I had thought of the internet as a basic tool that has the capacity to empower women and help us overcome the gender gap. But even as the number of internet users rises remarkably, there is still a significant disparity between women and men.[1] According to ICT for Women [a portal of Egypt’s Ministry of Communications and Information Technology], women constitute 46.5 percent of internet users in the country compared to 53 percent men (2018).

For large populations in less privileged areas and from less privileged class backgrounds, both in and outside of Cairo, access to digital spaces is limited. The lack of internet services in one Minya Governorate village, el-Barsha, explains one of its residents in a Facebook post, is due to the fact that the telecom base in the village (which would in theory providing internet services to its population) has not seen any upgrades since the era of British colonization. This has left people with no other option than to resort to individual, ineffective and costly solutions, such as monthly mobile internet subscriptions. For el-Barsha to get ADSL, a formal petition must be submitted supported by two thousand resident IDs, demanding the development of the telecom base. With this prohibitive condition in place, the village continues to be denied the right to internet access.[2]

My relationship with social media platforms first began in 2012, around the same time I started developing an interest in political organizing. My first social media interactions came to life with calls to protest, educational activities and political dissent campaigns, all utilizing social media as a tool to promote certain politics. Social media also contributed to my personal growth, and what I mean by growth is beginning to realize different aspects of my identity entangling; I was finding out that my gender identity was not separate from my political views on public affairs and forms of governance. I remember that the turning point was the mass sexual harassment and assault incidents that took place at protests in Tahrir Square and other places. It was quite the juncture in my personal journey, even in the development of my political beliefs. People speaking out publicly about mass sexual harassment and assault were met with denial on the part of a lot of comrades and other activists who blamed the regime for orchestrating these attacks. They claimed the state was inserting informants to harass women in order to defame the protesters or tarnish “the reputation of Tahrir Square.” This narrative comes with the implied claim that protesters are incapable of committing such acts — as if our comrades were alien to patriarchal Egyptian society, as if they had not been socialized since birth into its misogyny, its discriminatory attitudes and practices toward women and people with non-conforming identities.

A taskforce was formed in November 2012 to combat mass sexual harassment and assault: Operation Anti-Sexual Harassment (OpAntiSH). Communicating and organizing online, they intervened in incidents of mass sexual harassment in Tahrir Square and nearby protest locations. OpAntiSH found that most mass incidents were organized, and not removed from the general sexual harassment that is pervasive in society, or from the exclusion of women from the public sphere and political movements.

Fast forward to 2017. Some months before #MeToo spread, with versions in different languages, inspiring feminist solidarity and support across borders, Egypt had its own hashtag. #أول_مرة_تحرش (‘The first time I was sexually harassed’). Women from all kinds of social, economic and religious backgrounds shared their stories with sexual violence in the public sphere, as well as in their private lives.

As street action died down, various networks of individuals and groups were established to address specific issues: emotional and psychological support networks for people dealing with chronic pain, where they share experiences and information; knowledge sharing networks to exchange information on health services, such as abortion; and women’s networks, through which they are encouraged to look after their mental health as a form of support, and lists are shared of psychiatrists and psychologists who are aware of some of the challenges we face.

I followed online feminist activity. Kohl Journal “trouble[s] the hegemony of knowledge production” with Arabic-language material on gender, sexuality and feminism from an analytical perspective and through an intersectional lens. Another platform provides emotional support to women who have faced domestic violence, as well as information to girls and women living on their own (mustaqillat). Al-Qaws for Sexual and Gender Diversity is founded in resisting colonialism and the longstanding system of Israeli apartheid in Palestine, through the development of an understanding of the forms of repression and exclusion faced by women with marginalized and diverse gender and sexual identities. The A Project offers a Sexuality Hotline (via phone and email), providing information and support on sexual and reproductive health, contraception options, HIV, and gender and sexuality in general.

My former perception of the internet — as an open space where people can express themselves and overcome the gender gap — had been shattered. I began to view the internet as an extension of reality, especially in the way it reinforces patriarchal and misogynistic practices. It is just as it feels on the street for people with non-conforming sexual and gender identities, but maybe it is even more harsh, lonely and violent. Women are careful what parts of their lives they share online — not only for fear of cyberbullying and harassment, but also of the authority wielded by family and relatives, who are present in the same space. Like every other social setting, the internet has come under the sway of moral surveillance and self-censorship.

I became quite aware that the very fact that I can engage in an online argument to advocate my position on something as personal as the right to abortion is in itself a privilege. It is like discussing a socially unacceptable topic over dinner with your family and relatives; it is very difficult to talk about women’s right to abortion in such a setting. And even if I manage to spark up an online conversation about such a topic, I find myself having to proofread any comment multiple times to avoid having the conversation derailed on the basis of syntax. I also find myself having to cite numerous scientific findings and evidence to support a view about something related to my own identity and body, because I know that my account alone is not enough.

I grew exhausted and frustrated; spaces were increasingly suffocating. And as on-the-ground organizing and activism were thwarted, security surveillance extended from the street into cyberspace by means of social bots, and there were many arrests based on online political activity. Conventional organizing techniques became unviable in the current political climate. To adapt, we embraced different tools to organize in new and different spaces — and my definition of these tools changed.

I altered my online habits. I no longer took part in extensive commentary and analysis of the context where I live. In an attempt to preserve my mental wellbeing and maintain my emotional composure, I stopped engaging with the perpetual flux of political events in the Egyptian arena. As a result, I’m sometimes accused of indifference or not caring about public issues, with the implication that I sold out.

For example, I made a deliberate decision to refrain from expressing my opinion on the serial sexual harassment perpetrated by a player on the national Egyptian football team, which came to light during the 2019 Africa Cup of Nations. One of the survivors disclosed a sexual harassment incident she experienced, and several other claims of sexual and online harassment by the same player followed. The reactions on social media filled me with rage. People vilified the survivors, others commented on their appearance, others still promoted a conspiracy theory about there being an effort to tarnish the public image of the national team as well as the Egyptian state.

My approach was based in the conviction that it is futile to reiterate the most basic definitions over and over again, as I used to. I resolved not to explain any obvious points about what sexual harassment is and what constitutes an act of aggression in my view. A second aspect to this approach is not to engage with the specifics of any incident but to share my renewed personal frustration with the fact that something as glaringly evident as the sexual violence women face on a daily basis still needs to be explained.

Sharing knowledge on violence against women — such as sexual harassment — and making it available online to all (especially to comrades, so as to equip them to address sexual harassment in the future) is a political act. I do it by highlighting the personal challenges that we face, engaging in every controversy over a harassment incident disclosed on social media, and sharing definitions and relevant literature on sexual harassment and the tools to fight it. Acting upon the belief that the personal is political is ultimately inseparable from the broader cause.

But as an attempt to preserve the very little energy I have left, maintain my mental wellbeing and avoid burning out in an unforgiving setting, I have carved up alternative spaces where I can let off steam and share whatever I want and feel, even unwanted feelings — about the weather, about Cairo traffic, my anger, my love for and gratitude toward feminist groups in Lebanon, Mexico and South Africa.

The internet is indeed used to share and propagate knowledge, but also to cultivate a certain image of ourselves. We always wish to control what we show others, and we expect to be able to gain that control via social media. This manifests itself in selecting the photos we share; they are retouched to be more beautiful. Here, an inescapable set of criteria arises, imposed by a heterosexual capitalist system that gets to define what is ‘beautiful’ and what is ‘ugly’. These beauty standards hurt us, though their violence is less apparently severe than the other kinds of violence we live with.

We continue to share bits of our daily lives, our wins, as well as our negative feelings via digital and social media. We choose these spaces as a means of contact, to make our non-digital reality less brutal and lonely. We sometimes share a personal update or a funny meme — not because we are happy and free of things weighing us down, but because we are struggling to survive. For that, we need to escape our reality every once in a while. In that sense, digital space may be seen as a reflection of our identities, experiences and lived realities in all of their different aspects. That inevitably means current political events, economic conditions and society with all its complexities and challenges — and the countless moments of dark comedy in our daily lives.

Lately, however, I’ve noticed an uptick in my social media activity. This can be attributed to the Lebanese uprising, led by feminist comrades I know and love. I have been following their political feminist movement, a movement that does not invoke the “priorities” rhetoric, a movement that includes people of all social backgrounds and classes. I see transwomen and transmen supporting the uprising and raising their civil rights issues. I see mothers and grandmothers demanding social change. I hear intersectional chants for radical change and social justice for mothers, sisters, wives, transwomen, workers, refugees. I witness all of that via the internet from a geographically remote location, and find myself sharing these videos and posts with such energy that I had not felt in a long time.

The challenge we face today is to connect different groups — especially women, gender non-conforming people, and those with non-conforming sexual orientations — to establish feminist policies and principles that would make the internet available to women in their native or preferred languages, provide them with the kind of content they want, create spaces for self-expression without fear of online harassment, generate equal opportunities for women in tech fields and encourage them to venture into them. As feminists we have utilized digital spaces to build new identities and cultivate relationships across borders, thus enjoying a bit of freedom. For me, I’m concerned with creating a supporting “feminist internet” that exists in an international context. And as Egyptian feminists, each of us comes from a different margin.

What I aspire to do is to contribute to making the internet available, to extending solidarity networks that promote feminist consciousness of the regime under which we live, the regime which further bolsters violence against, marginalization of, and discrimination against women of color, women with non-conforming gender and sexual identities, women coping with physical disability and mental anguish, and so on. I believe in the importance of knowledge accumulation on the path to building a passionate, conscious feminist movement that breaks from the dominant, generating different narratives of our different histories and experiences. I see a need to document our feminist struggle and resistance by offering the narratives of our margins. This is how we create knowledge that helps build a feminist movement, leading to social change by women for women.

[1] Views and perspectives on gender rights online for the global South: “Redefining rights for a gender-inclusive networked future,” Association for Progressive Communications, July 2018, https://www.apc.org/en/pubs/views-and-perspectives-gender-rights-online-global-south-%E2%80%9Credefining-rights-gender-inclusive

[2] El Barsha, 5 October 2019, Facebook post.